“It depends who is doing what”, I would say.

Timothy Doner is now (2014) 18-years-old. He lives in New York and mastered himself 23 languages, each one in just a few weeks.

Cardinal Mezzofanti -who lived two hundred years ago in Italy- learnt and fluently spoke 38 languages without travelling out of Italy.

In both cases there was an individual innate aptitude joined with a deep love for learning and a strong commitment to it.

Individual factors – such as personal talents, enthusiasm for learning and determination to reach an achievement – have a significant influence on your speed of learning. For the majority of people, language learning is a complex process that moves through various stages over a certain time span, where the individual speed of learning should be considered in relation to other factors rather than on its own.

Let me group all those factors in two main categories:

- Individual circumstances

- Language learning process.

Part 1 - Individual Factors

AGE– It is well known that young children can learn a second language easily when exposed to the language either within the family or in a social context.

Older learners can also be successful in language learning but they might need more time, might struggle more, especially when trying to achieve the correct pronunciation and fluency.

PERSONALITY – An outgoing personality is more likely to take the risks of speaking and communicating with no fears of mistakes.

He or she can smile on errors and can work on THEM to learn more.

People with an outgoing personality tend to communicate with others even if their vocabulary is poor or they don’t know the grammar. They communicate through empathy somehow, using all their resources: gestures, expressions, synonyms, key-words of their native language mixed with their second one.

They spontaneously interact more with native speakers and find a channel for communication. They gain therefore more practice and more confidence in speaking their second language.

An anxious, shy learner on the other hand is more likely to stay alone, to avoid any “embarrassing” situation, fearing that he or she can neither understand nor communicate.

The improvement for these characters is going to be much slower…

MOTIVATION – When learners want to improve their language skills for their own development and convenience (for a future job opportunity, for a school achievement, for communicating with friends and relatives, etc), they will be more determined to achieve their targets and will enjoy learning, even when struggling, Their improvement would be much faster and more evident.

MOTIVATION – When learners want to improve their language skills for their own development and convenience (for a future job opportunity, for a school achievement, for communicating with friends and relatives, etc), they will be more determined to achieve their targets and will enjoy learning, even when struggling, Their improvement would be much faster and more evident.

When a student “has to learn English” because is pushed by external factors, the engagement will be weaker and he or she would likely be careless of achievements…

EXPERIENCE – Learners who are used to travel, to interact with people of different nationality and culture, to relate and communicate with friends of other countries, are more likely to improve quicker than those who do not get out of their village until late in life.

NATIVE LANGUAGE – It is easier to learn a language of the same language family: a German or Dutch or Swedish learner will find more similarities with their mother tongue when learning English than a student from Spain or France or Italy. The improvement will be broader and faster for those learners whose native language has the same root of the studied language.

ENTRY LEVEL – Learning a language is not as simple as to receive one notion, store it in our memory and use it when needed. It is a much deeper and wider process that affects the whole personality and involves mental as well as emotional and even physical energy.

Young leaners often need more sleep, especially in the first days of living abroad.

OTHER INDIVIDUAL CIRCUMSTANCES – The general aptitude for learning may also have a relevant part in defining the pace of individual progress.

Part 2 - The process of language learning

As mentioned, language learning is a complex process that develops through different levels and stages and involves the acquisition of new language structures for understanding and speaking. It means that our way of thinking needs to adjust to the new language structures. In other words the acquisition of a new language is not learning to translate what we think in our native language into the new one, but to think directly into the new language. Such a change it doesn’t happen overnight for the large majority of learners.

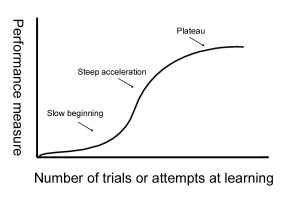

If we look at the curve of learning, we can see that in each stage there might be a different speed in learning and a different visibility of the improvements achieved in a certain time frame.

The first part of the curve rises slowly, then increases sharply in the middle and finally grows slowly again at the top end (“learning plateau”).

Total beginners, therefore, may appear to be slow and not showing much of what they have absorbed. They need to build up a vocabulary, essential communication routines, basic language structures: they seem ‘passive’, but are actually nourishing and enhancing the soil on which the language can blossom.

Total beginners, therefore, may appear to be slow and not showing much of what they have absorbed. They need to build up a vocabulary, essential communication routines, basic language structures: they seem ‘passive’, but are actually nourishing and enhancing the soil on which the language can blossom.

When learners start a language programme having already achieved that first stage, their improvement is generally quite fast and well visible even in a short stay.

After that ‘breaking-point’ the language can improve sharply at the most advanced level having no upper-limit: we can indeed improve our language for the entire life.

This trend can be experienced in several learning processes -not only in language learning-, when we compare the increase of proficiency with the time of learning.

The learning curve depicts a trend whose gradient may vary at any point according to the individual circumstances listed above.

Let’s have a more detailed insight of those stages.

On the lower end of the curve the improvement is very small. This is the first stage when the learner needs almost to listen the new, unfamiliar language. If a learner starts a language programme during this first period, the improvement in that period will generally be not very evident: yet, there is a silent progress and it is extremely precious!

This stage is called the “silent period” when learners are almost “listening”.

Listening is the first, most important “passive” activity in language acquisition. The younger you are when you go through the initial stages of language learning, the most effective is the unconscious acquisition of various aspects of the language: phonetics, meanings, language structures, all “stuff” that the learner absorbs without thinking but will use later on when ready for it.

Listening is the first, most important “passive” activity in language acquisition. The younger you are when you go through the initial stages of language learning, the most effective is the unconscious acquisition of various aspects of the language: phonetics, meanings, language structures, all “stuff” that the learner absorbs without thinking but will use later on when ready for it.

The “silent period” can’t be dropped out. If you start learning English at the age of 25, you still need to go through the initial stage and may be surprised of how much time and efforts it requires. For a beginner adult, the first stage of learning might be not as easy as it is for a 4-years-old child!

Gradually, the learner begins a basic production of language using key-words or short sentences. At this stage the vocabulary might reach about a 1000 words.

A sudden sharp turn-up occurs when the speech emerges in simple sentences, basic communication routines and a vocabulary rising to 3000 words.

After this turning point the improvement speeds up to a certain fluency with more complex sentences, the capability to communicate and share thoughts and opinions, understanding of contents in various areas and media and a vocabulary increasing to 6000 words about.

Finally the learner reaches the level of advanced fluency which is a stage close to a native speaker, when higher levels of language proficiency are achieved and ready the access to advanced academic contents.

In a previous article I looked at the language acquisition process from a different perspective, that is observing new-born babies. If you are interested, read more here.

CONCLUSION

Now we can return to the initial question of much English I can learn in one short-stay course (2 or 3 weeks).

The answer is not a simple quantification of your proficiency. You can honestly find a personal answer considering your position in relation to all the factors mentioned, thence you can see what to expect.

You should also be aware that your school level of English might be slightly different from your real ability to use the language, especially the spoken language.

This is exactly what AEL stands for:

- becoming capable to use your language cognition and personal talents

- improving your communication and language skills

- helping to transfer your bag of academic knowledge into a learning environment that will not only facilitate your language improvement but also nourish your personal development.

A short course should be seen as one step in the whole process of language learning, let’s say a homeopathic dosage not less effective than a longer programme.

When you go abroad for 12 or more weeks, you can obviously move from an elementary level to a good one.

AN ORGANIC RHYTHM OF LEARNING

On the other hand, repeated short language courses may lead you to the same level with the benefit of eventually been more organic to the needs of children and teenagers.

We can indeed take into consideration the intervals between repeated experiences: in those intervals there are months, when learners can assimilate what they did take in during the summer school and can discover new enthusiasm, new motivations and more commitment to learn English while waiting for their next experience.

I have witnessed learners who have repeatedly come to AEL for two or three summers and learnt to speak English, becoming fluent and capable to communicate with confidence just being in short stay courses. One of the learners is Linda who wrote a clear report of her experience on our website in her feedback: she came for five summers in a row for 2 or 3 weeks each summer, starting from the very shallow end of the curve up to a good capability to speak and hold a conversation with a native speaker.

Most of the students have been studied English at school before coming to the UK, but for many of them only their stay in the UK made their knowledge alive and ready to use, while before it seemed to be locked into their brain like a pair of glasses into a large ‘suitcase’.

What I recommend is to avoid only one short experience abroad: parents who want to invest on the future of their children, should plan a path for the acquisition of the English language, if they want their investment being productive. They might choose various providers and places, but it is wise to draw a path for language learning for their own best.

The younger, the better; but it is never too late!

vr, april 2014

[images from “How to be British” collection One and Two – sold by Amazon and btwostore]