The mental health crisis

Between 2010 and 2015 an unexpected wave of mental health issues stormed children, teenagers and young people as it was never seen before.

In his recent book “The Anxious Generation”, released in March 2024, Jonathan Haidt analyses what happened in those years when teenagers began to say that they felt “sad, empty, depressed” or “lost interest with things that they normally enjoyed” and why young generations -in particular Gen Z- were affected by that wave of mental health issues at such an acute rate.

The data collected by Haidt from 2010 onwards about mental health issues in children, teenagers and young people are absolutely shivering:

- depression grew by 145% in girls and 161% in boys (12-15);

- anxiety rose by 139% in young people (18-25);

- self-harm incidents in children (10-14) increased sharply by 188% in girls and 48% in boys;

- suicide rates among the same age group (10-14) went up by 167% amid girls and 91% in boys

Living online

Haidt gives evidence that the main factor for such a dramatic increase of mental health issues has been the massive expansion of smartphones and social media that found families and schools fully unprepared.

He notes that -when in the 90s personal computers and basic mobile phones rapidly invaded the market- there was no sign of decline in adult’s or children’s mental health.

Basic mobile phones (also called “brick phones”) were primarily designed to make one-to-one phone-calls and send short text messages with a complicated typing method (one key had several values in it and you had to press that key one to four times to get the wanted value).

Smartphones instead can connect you to the internet 24/7, run unlimited apps and have become the favourite house to social media.

And, we now know that social media are designed to exploit human vulnerabilities as Sean Parker candidly declared to Axios in 2017 and the Netflix documentary “The Social Dilemma” confirmed in 2020,

The great rewiring of childhood

Many adults jumped on the new digital progress in uncritical mode and made those magic devices and their apps available to their children, unaware of the impact that they would have.

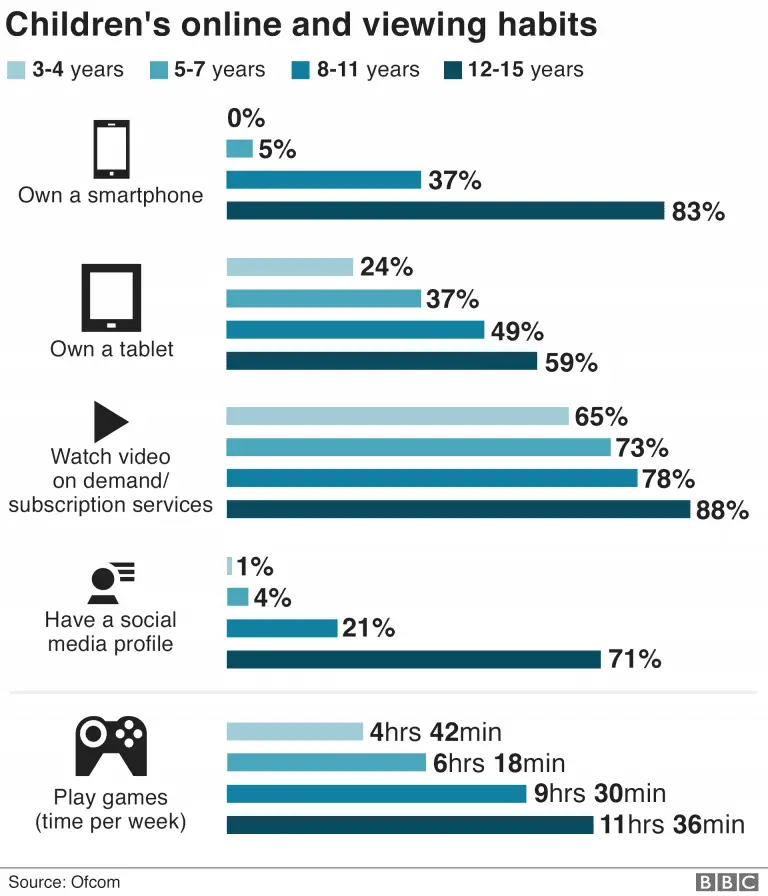

With smartphones and social media in their hands, children and teenagers started their “online life”, isolated in their rooms, socialising online instead of going out to meet friends, playing video games with a few fingers instead of playing freely and creatively indoors and outdoors, watching videos of any kind day and often late in the night.

The “poisoned boxes” -as Haidt call them- were allowed to enter many houses and deprived children and teens of real life experiences causing the crisis that is still moving sharply upwards.

Haidt calls this transformation “the great rewiring of childhood” that took children out of their “play-based” childhood to push them into the “phone-based” childhood”.

Do we protect children offline more than online?

Haidt thinks that parents contributed to the mental health crisis (and still do) when they prioritise the protection of their children from the risks of real life experiences but do not pay the same attention to the protection of their children’s “online life”.

In his words, parents are over-protecting their children in the real world but are under-protecting them while they are online.

This thesis might cause a grimace of discomfort in some parents, but I think it should be considered with honest and serious attention.

Is it true -we may ask ourselves- that we parents are more concerned for a child climbing a tree than a child sitting on the sofa with a smartphone?

Do we overwhelm children with our anxiety when we limit them to play freely indoors and outdoors? Do we give them the space to explore their own creativity and independence as appropriate for the age?

Or do we prefer to see them sitting and laying quietly staring at a screen?

If this is the case, we should reconsider our assessment of risks to include what is happening when they are silently watching and playing online.

A similar review of risk assessment should be done when our young teens want to do things on their own but we are instead reluctant to let them go.

As a parent, I fully understand those worries and concerns as we live in times that are less child-friendly than we knew.

Still, we parents needs to distinguish what are the realistic risks of a situation in real life and where our own anxiety becomes a paralysing factor that denies them the experience of an appropriate level of independence.

Haidt’s highlight of this topic could be an opportunity to explore how a parental role is changing and what new educational responsibilities the current situation is calling on us all.

What happens when parents use the phone a lot?

Out of Haidt’s book, may I approach this question from a different perspective, that is not looking for a moment at how children and teens use their phones, but how we parents do.

How much time do we spend on the screen? And what do we use our phones for?

It is known that when parents spend a lot of time on screens -whether for work or entertainment-, their kids tend to do the same.

The connection that parents have with their smartphones, social media and internet models in fact how their children relate to their devices and in general how they relate to the online world, thus influencing their relation with the offline world too.

Parenting needs nowadays to pay attention for details that in the past might have been ignored.

What might be a good practice for parents?

For example, when children -before the internet- were unsettled, parents or carers were trying to divert their attention whether a toy or another activity.

It is nowadays very easy to offer unsettled children a screen as calming remedy and make them magically quiet!

It is indeed very convenient to transfer an unsettled child from the fuss of this world to the quietness of the online dimension through a smartphone, tablet or whatever screen.

Parents and child-carers, however, should never use the screen as calming remedy.

They shouldn’t even keep their phone at hand to immediately reply emails or notifications.

When at home, parents should instead focus on the relation with their children.

The younger the children are, the more they need parents talking, interacting and being present to the family dynamics.

In the evening, we make sure that the dinner table is a mobile-free zone as much as we ask for schools to be.

What counts, is that there are moments and spaces in the family life where phones are set away and parents focus on the interactions with their child or children.

Are we perfect Parents?

We are not…

We might draw in our mind the best intentions and rely on excellent advices, but daily life is very challenging: we might face a struggling time, a stressing day, we might just be tired, so we are not always able to apply our good propositions at perfection.

How many times do we arrive at home exhausted and buy time for ourselves by giving our child some screen-time? It happens, isn’t it.

When that happens, do not panic, do not feel upset or guilty: everything can be recovered and children are always ready to forgive our weaknesses.

In this case, you may find a corner of the house where you spend a quiet time together, have a chat, read a story, play a game, listen to music together.

Take whatever time you can to be with them: but , when you are with them, BE with them!

Would a legislation protect my child?

Yes, it would.

In the UK the Online Safety Act has been approved one year ago and will come into force in 2025. The Act provide OfCom with more powers to control and fine firms that do not comply with the provided codes and guidance in regard to illegal harms, pornography, age verification and children safety.

The most important measures include robust age checks, safer algorithms, effective moderation systems to take quick action on harmful content.

In US the government has also made the online protection of children a top priority and two proposals are at the moment under consideration: the Kids Online Safety Act, which would require social media platforms to restrict access to minors’ personal data, and the Protecting Kids on Social Media Act, which would rise the minimum age for using social media platforms.

There are also initiatives in various countries, aiming to promote a normative that regulates the children’s online safety.

Last week (October 2024), a Labour MP, has put forward a private member’s bill -that he called “seatbelt legislation”- to protect the children’s online life. In February 2024, the Tory government issued a ministerial guideline inviting schools to outline a regulation for the use of phones.

At the present over 60% of schools in the UK chose a total or partial ban to the use of mobile phones.

All those initiatives are surely welcomed and a working legislation would be of great support for parents and schools.

However, a legislative framework alone would not be sufficient to change the current trend of rising mental health issues.

Nor it would repair other negative effects that are well visible at home and in classrooms, such as reduced concentration, lack of focus, weakness in social relations, sleepiness during the day and that particular condition of “not-being-there”, induced by the use and misuse of smartphones, social media and the general “online life” with its content.

The quality of content is in fact one of the most critical points for a legislation to be effective.

Let me reiterate that, although a legislation would implement the online protection of children and provide some support to schools and families, there is no doubt that parents should still engage more intensively in the education of their children, regardless what it might happen at lawmakers’ level and expand their role to the protection of their children offline and online.

Furthermore, parents should consider to be extensively involved in children’s real lives to accompany them to rediscover the beauty, the interest and the passion for the offline human reality over the illusionary online life.

A foundation to change the trend

The final chapters of the book “The Anxious Generation” are full of suggestions and recommendations for schools and parents and can essentially be summed up into four fundamental guidelines.

May I cite Haidt in full in this section:

“…there are four reforms that are so important, and in which I have such a high degree of confidence, that I’m going to call them foundational. They would provide a foundation for healthier childhood in the digital age. They are:

1. No smartphones before high school. Parents should delay children’s entry into round-the-clock internet access by giving only basic phones (phones with limited apps and no internet browser) before ninth grade (roughly age 14).

2. No social media before 16. Let kids get through the most vulnerable period of brain development before connecting them to a firehose of social comparison and algorithmically chosen influencers.

3. Phone-free schools. In all schools from elementary through high school, students should store their phones, smartwatches, and any other personal devices that can send or receive texts in phone lockers or locked pouches during the school day. That is the only way to free up their attention for each other and for their teachers.

4. Far more unsupervised play and childhood independence. That’s the way children naturally develop social skills, overcome anxiety, and become self-governing young adults.

These four reforms are not hard to implement—if many of us do them at the same time. They cost almost nothing. They will work even if we never get help from our legislators. If most of the parents and schools in a community were to enact all four, I believe they would see substantial improvements in adolescent mental health within two years. “

Awareness is the educational compass

These suggestions from Jonathan Haidt are a good foundation to think about the challenge that young generations are facing and that is going to become sharper with the uncontrolled introduction of AI in all sectors of life.

It would be also effective to discuss and share any problems with other parents and teachers and ultimately to raise awareness about the conflictual world that current technology is generating, for awareness in education is a good compass to guide our daily behaviours and decisions.

I strongly recommend the reading of Haidt’s book as it may also inspire parents and teachers to a sensible approach to the growing intrusion and control of the digital technology into our children’s lives.

VR

In depth >

Read more to deepen your insight of the mental health crisis in children, teens and young people: